Roda Viva (Wheel of Life) is a mixed media installation about uncertainty and impermanence, with imagery and themes inspired by the song Roda Viva by Chico Buarque. Made with charcoal and acrylic paint on 400 pieces of cardboard, the work was temporarily installed on a 30 foot wall using paper and masking tape.

Roda Viva was composed and performed by Chico Buarque, a Brazilian singer, composer, playwright and writer. Much of his work includes social, economic and cultural commentary, particularly on Brazil. Buarque’s Roda Viva refers to the “wheel of life” which forever turns, creating turmoil and carrying life’s ambitions and accomplishments away.

Buarque composed the song in 1966 as commentary on the dictatorship in Brazil, with the “wheel of life” serving as a metaphor for the authoritarian regime that deprived working-class Brazilians of their dreams of freedom and democracy. While many of the allusions to politics and personal expression are relevant to the time the song was composed, the themes are just as relevant today considering the political turmoil in Brazil and throughout the world, and the environmental and climate crises humanity is facing.

Before I began studying the lyrics, I became obsessed with the elaborate harmonies of Roda Viva and how Buarque constructed the catchy melody throughout the song, I eventually realized the song was about much more than I thought, with serious commentary on the struggle between human desire and longing and how forces outside our control can upend our lives, and felt inspired to incorporate those themes into my own work.

Four panels

As it was installed, the Roda Viva mural is composed of four interconnected panels that are inspired by themes from the verses of the song: Destino (Destiny), A Baiana, A Roseira (The Rosebush) and Saudades (Longing).

Destino (Destiny)

| Tem dias que a gente se sente Como quem partiu ou morreu A gente estancou de repente Ou foi o mundo então que cresceu? A gente quer ter voz ativa No nosso destino mandar Mas eis que chega a roda-viva E carrega o destino pra lá | There are days that we feel Like those who went away or died Did we suddenly stop Or was it the world that grew? We want to have a say Make our own destiny But then arrives the wheel of life And carries destiny away |

In the first verse, Buarque sings about the human desire to control our destiny and create change in our lives, but the world changes and grows and our destiny is lost, making us feel like we’ve been left behind and struggled for nothing.

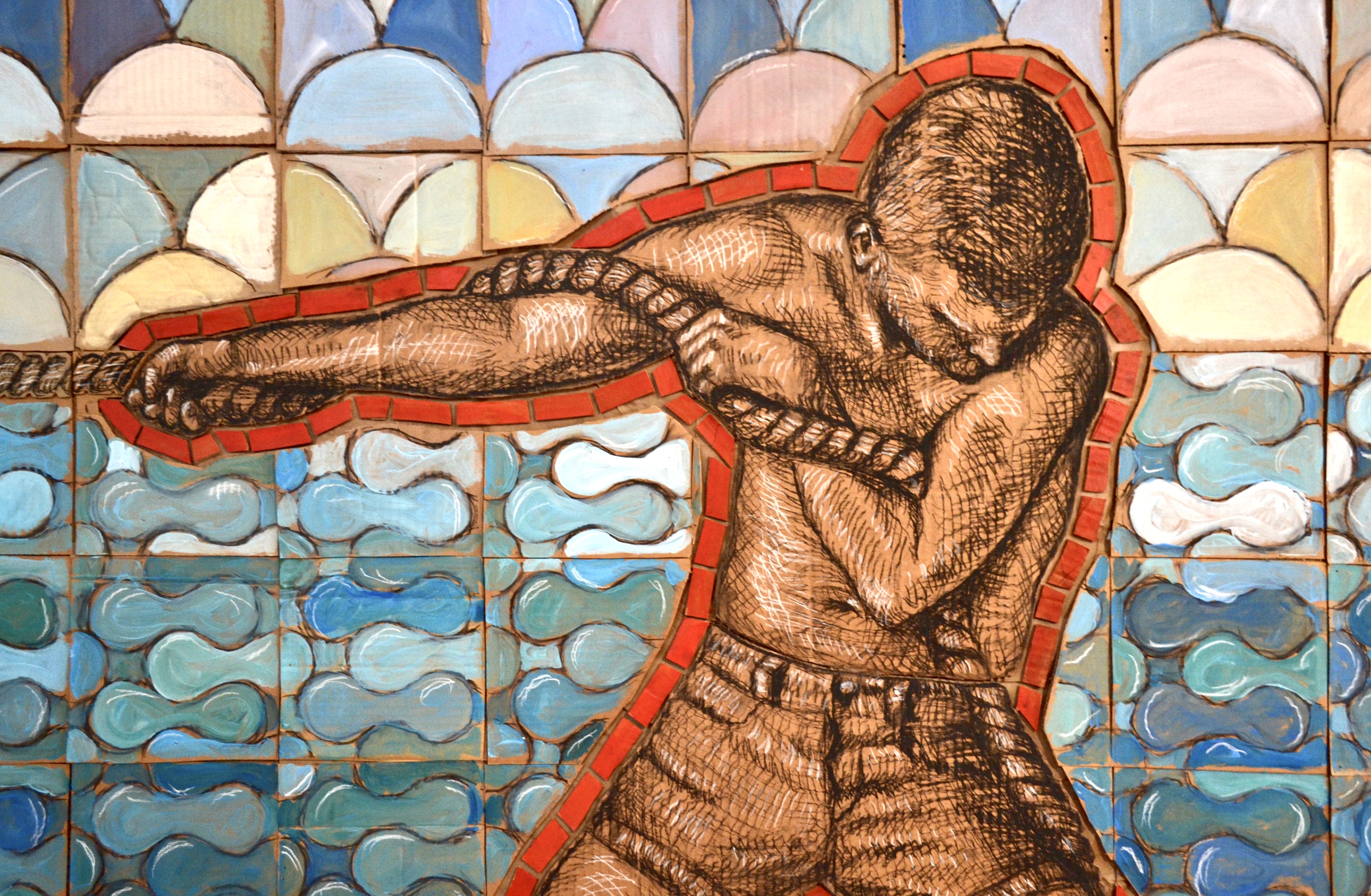

In this frame of the work, the figure pulls against a force that is out of view, making it unclear if progress is possible and what is to be gained. On the ground are notebooks representing a life of introspection and documentation, but now underfoot, easily lost and forgotten.

The rope is a continuous thread throughout the work, symbolizing the path our lives take and how that path surrounds and carries us a long even as we try to control it. The background of each panel also features cardboard “tiles” with designs inspired by “azulejos,” a ceramic tile decorative art common in Brazil. The designs in Destino are divided in thirds and represent an abstract landscape, with patterns representing earth, water and sky.

A Baiana

| A roda da saia, a mulata Não quer mais rodar, não senhor Não posso fazer serenata A roda de samba acabou | The turn of the skirt, the mulata Doesn’t want to turn any more, no sir I am not able to serenade The samba circle has ended |

The second panel is inspired by the second verse of Roda Viva, about the dancers and musicians who have been silenced, the samba ended. Under the dictatorship, speech was restricted and dissidents jailed and tortured.

Throughout Roda Viva, Buarque uses metaphors and allusions to Brazilian culture to express his views and subvert the limits on self-expression and was a victim of repression when his play, also called Roda Viva and featuring the song, was violently attacked by a paramilitary group that supported the dictatorship,

In this panel, the Baiana (literally, a woman from the Brazilian state of Baia) wears a traditional white dress, featuring a hooped skirt, a shirt embellished with lace and embroidery, a shawl, and an oja, a cloth tied around the head. The clothes have spiritual significance and the skirt, or axó, represents the Baiana’s status in Bahian culture. A contingent of dancing Baianas are a main feature in parades during carnaval, with the traditional white clothing transformed into elaborate costumes in brilliant colors.

A Roseira (The Rosebush)

| Faz tempo que a gente cultiva A mais linda roseira que há Mas eis que chega a roda-viva E carrega a roseira pra lá | For such a long time we cultivate The most beautiful rose bush there is But then arrives the wheel of life And carries the rosebush away |

In the third verse, Buarque sings about cultivating a rose bush, but with the passage of time, even the most beautiful bush will burn and and be carried away. No matter what we accomplish in life, it too passes.

In this frame of the mural, two rose bushes are intertwined, one alive with blooms and the other dry and dead, representing the interconnectedness and interdependencies of life and death.

Saudades (Longing)

| No peito a saudade cativa Faz força pro tempo parar Mas eis que chega a roda-viva E carrega a saudade pra lá | In our hearts our longing is captured Pushing hard to stop time But then arrives the wheel of life And carries the longing away |

In the final verse, Buarque sings about saudades, a word in Portuguese that doesn’t have an exact translation in English, but speaks of longing we have for all that has past in our lives. We cling to our past, trying to stop time, but once again life turns and our longing too is lost.

The figure in this panel is distracted by the past but continues walking forward, nearing the end of rope, a lifetime complete. The figure is accompanied by a bird, a European bee-eater, which pursues its’ prey, representing a longing for nature and the end of nature as we know it.